Acupuncture, an Asian healing technique with more than 3,000 year old, which has been the subject of various researches, the most outstanding are those related to incontinence and female infertility.

A research team found acupuncture did improve symptoms of stress incontinence -- an involuntarily loss of urine, such as when a woman sneezes or coughs.

But in a separate study, another team of researchers determined that acupuncture did not help women who were infertile because of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Women with PCOS have a hormonal imbalance that keeps them from releasing an egg (ovulating) during the menstrual cycle.

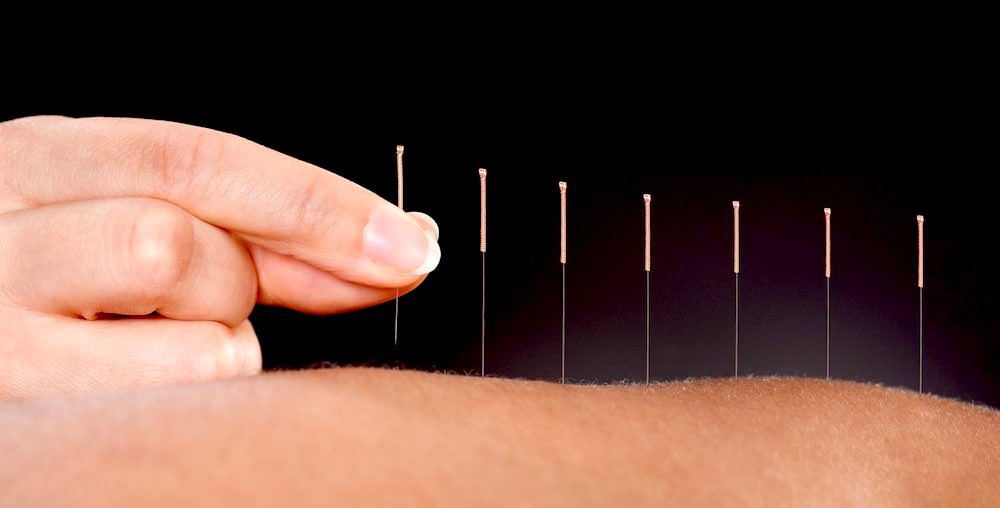

Acupuncture is a key element of traditional Chinese medicine. It involves inserting thin needles into the skin to stimulate specific body points. Previous research has found it might benefit constipation, depression and morning sickness, among other problems. And some research has found it helpful to boost fertility when the problem is not due to polycystic ovary syndrome, the researchers said.

The bottom line from the two new studies?

"The research on acupuncture for stress incontinence suggests that acupuncture could be a reasonable and low-risk approach to try before attempting riskier, more invasive treatment such as surgery," said David Shurtleff. He's deputy director at the U.S. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine and co-author of an editorial commenting on the two studies.

For infertility due to polycystic ovary syndrome, however, Shurtleff said acupuncture has not been found effective. He suggested patients consider other options.

More rigorous research on acupuncture is needed in general, he added.

For the incontinence study, researchers randomly assigned about 500 women to 18 real or sham electroacupuncture sessions -- acupuncture involving electrical stimulation. The average age of the women was 55, and the half-hour appointments occurred over six weeks. The needles were placed near the small of the back and the back part of the pelvis between the hips.

At six weeks, women who received the real acupuncture had less urine leakage, the study found. These results persisted for another 24 weeks without treatment.

Measuring incontinence over 72 hours, the researchers also found that nearly two-thirds who received real acupuncture had had a decrease of 50 percent or more in the amount of urine leakage.

The treatment may work in a number of ways, said study leader Dr. Baoyan Liu, a researcher at the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences in Beijing.

Acupuncture may strengthen the pelvic floor muscles, among other things, he said. This "may also account for the [persistent] effect" after treatment ended, he added.

Liu can't say if acupuncture would be better than drugs to treat incontinence, as the researchers did not compare acupuncture to drugs. However, acupuncture may have fewer side effects than drug treatment, he noted.

The other trial involved 1,000 women with polycystic ovary syndrome, a condition that affects 5 percent to 10 percent of women of reproductive age, according to background notes with the study.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four groups: real acupuncture plus clomiphene, a drug used to induce ovulation; fake acupuncture plus clomiphene; real acupuncture plus a placebo drug, and fake acupuncture plus the placebo. The drug or placebo were taken for five days each menstrual cycle, for up to four cycles.

Acupuncture made no difference, with about 22 percent of each group delivering a live baby, according to the study. The corresponding author is Dr. Xiao-Ke Wu, who's with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine in Harbin.

However, the live birth rate was much higher in women treated with clomiphene, which was expected. While 29 percent of those who took the drug delivered a baby, only 15 percent of those on a placebo did, the study found.

The researchers concluded that acupuncture won't help infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

Both studies and the editorial were published online June 27 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Fuente: www.upi.com